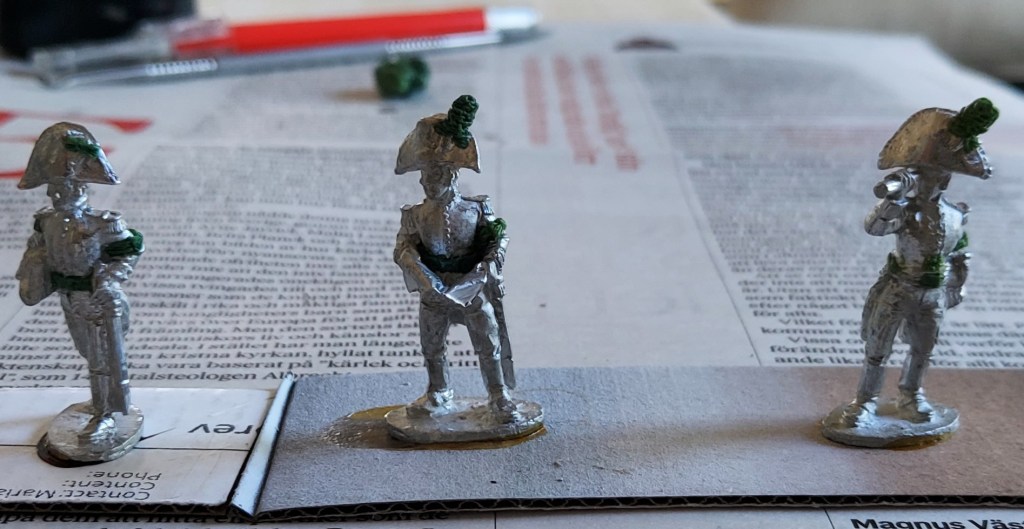

Just finished these colonels of the Västmanland and Hälsinge regiments. They will represent brigade commanders of the Swedish brigades at (for example) the battle of Oravais.

Dedicated to the fine art of historical miniature painting

Just finished these colonels of the Västmanland and Hälsinge regiments. They will represent brigade commanders of the Swedish brigades at (for example) the battle of Oravais.

I recently added new flags to the second battalion of the Västerbotten regiment which I have now completed apart from the basing. These flags correspond better to the historical information that I have gathered. I managed to salvage the old flag, which I painted after the old 17th century model. It may come in handy one day, as I do indeed have some appropriate 17th century miniatures in my unpainted pile…

Ive been meaning to do this for a long time. As I make my own flags for my Swedish and Finnish figures for 1808, I thought that Itd be a nice thing to share these. Especially since these flags are not available from many commercial outlets, and those that are available do not necessarily have the correct details and do not cover all regiments. Below youll find a few flags I have done recently, the idea being that the collection will grow over time. Feel free to use them in any way you like. I suspect that it could work quite well if one were to adjust the size, and print them with a good color printer on standard printer paper. Then cut them out and mount them onto the figures with PVA glue as you would ready made flags from GMB (or any other maker).

The flags are far from perfect, and I am afraid that the scans arent either. The 1766 king’s color has at least been updated with a better scan. For the rest of the regiments, Ill upload all the flags that I make as soon as I paint them.

Moving forward with more troops for my 1808 Swedes. This is the last of the Finnish regular regiments. I will need one large battalion of 30 or 36 figures plus som skirmishers. Painting six at a time go is a good way of working away at large numbers of miniatures at a reasonable pace.

Having painted around 300 of these Perry Swedish infantry, I have found a few tricks to speed up painting. First, I try to let the shading wash do as much of the work as possible. Highlighting makes figures look better, but it takes time – there is a definite trade-off. So if there is anything that can be done to minimize highlighting, that will be necessary, especially for rank-and-file figures, such as these. At the same time, one does not want to omit those effects that really make the figures look good. My solution to this is to use highlights where they really make a difference, and to leave them out where they dont.

Areas such as the blue of the coat, the dark grey of the gaiters and boots, leather straps, dark leather of the shoulder bag, dark hair, and also the musket wood and all metal fittings, buttons etc, work pretty well without further highlighting. When batch painting, I also do all of one batch with the same color of the hair. Next batch will have light hair!

As for the metal parts, I used to paint these black before painting in the metal color. Ive found that this step is unnecessary if you shade them with a wash as dark as AP strong tone, which is the one I use. For gun metal/steel, I mix the metal color with black. I also add one highlight to the steel of the musket. This is because I actually leave the top of the bayonet unpainted until the last moment. This is simply because I need to hold the figure, putting my finger on top of the bayonet while painting, which will inevitably lead to paint chipping off. So, better to leave that and do it at the very end, so that I dont have to re-paint the bayonet on every figure.

Yellow is a color that really needs highlights to look good, and on these particular figures, that means a large part of the clothing! The skin of the face and hands also look a lot better with highlights and they give the figures a great deal of their character. The black of the hat is also highlighted, as are the light patches on the shoulder bag. Over time, I have tried and tested which areas can do without highlighting, and which cant, but its still a learning process. On these Perry figures, I also paint the eyes, which I dont normally do on their counterparts, the Brigade Games Russians. This is because of how the figures are scuplted. On the BG figures the eyes are pretty much in shade by the hat, but also very difficult to get right. The conclusion is that painting the eyes on them is just not worth the effort The Perry minis have very well sculpted eyes which are extremely easy to paint. Painting the eyes on these six figures probably took less than five minutes. In many cases, the eyes, just like skin tones, contribute much to the overall character of the figures – but that is not always the case.

Quick painting guide:

After cleaning with a knife, I first primed the figures with Army painter’s (AP) Leather Brown (spray can). The base colors were then painted in. Areas of flesh were painted with Vallejo (Va) Dark Sand before painting the flesh color (it does not cover well). Over the base colors, a wash of AP strong tone was applied. I diluted it somewhat with water over the trousers. After highlighting, the figures were varnished with Winsor & Newton’s Galeria Matt Varnish.

Base colors (with highlights) were as follows:

Coat: Coat d’arms (Cda) Royal Blue

Trousers and facings: Va Gold Brown (highlight 1: Gold Brown; highlight 2: Gold Brown+White)

Gaiters and boots: Va Black Grey

Hat: Black (highlight 1: Black+Black Grey; highlight 2: Black Grey)

Shoulder bag, main color, and hair: Va Dark Rust

Shoulder bag, light patches: Va Dark Sand

Belts: White (highlight 1: White)

Steel: Cda Gun metal+black (highlight 1: Gun metal)

Brass: Va Glorious Gold

Copper water flask: Cda Brass

Musket strap: Va Hull Red

Leather strap: Va Leather Brown

Flesh: Cda Tanned Flesh (highlight 1: Tanned Flesh; highlight 2: Cda Flesh)

I have been adding some figures to my unit of Nyland dragoons, to get them up to 9 figures, which will be rebased to a new and more standard format. When doing so I also added a standard. Some literature, Törnquist in particular, claims that the regiment did not carry standards. Illustrations made ca 1804 by Adelborg, who served in the regiment himself, show that this is wrong. However, I dont know exactly what the standard or flag looked like. It may have been a typical dragoon flag (dragonfana, with split tails) or a standard square cavalry guidon. There is a preserved dragonfana for the Karelian dragoons (in the Armémuseum in Stockholm), but it dates to the 1740s and it does not seem to have been used by the regiment – presumably that is why it has been preserved. In any case, the motif is very likely to have been the Nyland coat of arms over a red background on one side and a royal monogramme on the other.

My standard is very much oversized, but so are all my flags! As you have probably already spotted, I missed trimming the fringes around the flag pole. I dont do many cavalry standards, so it was a rookie mistake. And it is unfortunately difficult to do anything about it now… And looking at some actual preserved Swedish dragoon flags, it does seem that the fringes did indeed run all the way around the pole! So maybe it wasnt so much of a mistake after all. And regarding the size: there are certainly 18th century dragoon flags in the Armémuseum collections that are fairly large. I found one example which is no less than 120×140 cm (not sure if that includes or excludes the fringes?). On the other hand, there is the image below, which show a very small standard, guidon or whatever it is should called.

The figures are of course by Perry miniatures. The standard bearer is a simple conversion of the NCO figure (the Perrys dont include a standard bearer in their packs).

These are my first attempts at making some members of the Gyllenbögel free corps, a volunteer unit composed of various ex-soldiers and civilians. It was created in the summer of 1808 and saw action at a number of battles. The figures are simple conversions from Perry AWI figures and a Brigade Games Canadian 1812 militiaman (if I am not mistaken). The converting and painting on these is very quick and simple and I hope to be able to make quite a lot of these shortly. They will be complemented with Finnish uniformed officers and NCO:s, plus a few uniformed soldiers mixed in. I will need three, possibly four battalions; the free corps will make up the equivalent of a small brigade. Apart from the above ranges of figures, Ill use Perry French (1814 national guard), Norwegian landevaern and perhaps some Spanish and Prussian (Landwehr) figures. Some of them will need no converting at all, such as the many figures wearing caps or no headgear at all as well as the uniformed men. One of the battalions will consist of a larger part of uniformed soldiers, representing the “sharpshooter” battalion, which consisted solely of escaped soldiers.

These figures are great ones to make and paint, each one is individual and one gets to be quite creative in making little changes to make them as heterogenous as possible.

As most of you who are reading this will know, the Perry miniatures range of (very excellent) Swedish figures does not (yet :-)) include generals or colonels. I have converted various figures for this purpose previously, as can be seen in older posts. However, those have been single mounted figures, meant as brigade commanders. In most rules systems, a main HQ or overall commander of the army is represented by a base of a small group of figures. These would correspond to a commander-in-chief with some adjutants or other attendants.

Now, I have been contemplating the possibilities of creating a command base of this kind for a while. A couple of years ago, I came across the exquisite Saxon divisional command set produced by Black hussar miniatures: https://blackhussarminiatures.de/produkt/napoleonic-saxon-divisional-command. These were sculpted, I believe, by the very skilled Paul Hicks, who also did the Russians I use for the 1808 setting. It was immediately clear that these figures wear uniforms which are similar enough to the Swedish model 1801, which was an exclusive form of dress worn only by the top brass, staff officers and a few other categories, but not the regular infantry or cavalry officers. Therefore, the set is well suited for conversion into a Swedish high command group.

There are only three significant differences between the Saxon figures’ uniforms and the Swedish 1801 model. First, Swedish officers generally wore their swords in a waist belt and never used the sash which most other nations’ officers wore. On these figures, the higher ranking officer with the telescope is wearing a sash, but the others wear waist belts, partly underneath the jacket. The sash therefore needs to be removed and some cutting is needed before a waist belt in the Swedish style can be added in green stuff.

Second, all Swedish officers wore a white arm band commemorating the coup d’etat of 1772. This continued until 1809, when king Gustav IV Adolf was deposed. Adding an arm band like this with green stuff is not very difficult, especially after some practice (by now I have done it a few times).

Third, Swedish bicorne hats had a slightly different cockade, which looked more like a rosette. They also had a blue and yellow plume above the rosette.

Otherwise, the uniforms of the Saxon commanders were remarkably similar to those of their Swedish counterparts. The jackets had decorations in gold lace on the collar, cuffs and around the chest buttons, according to the logic of opulence: the higher the officer’s rank, the more gold lace they sported! Epaulettes had, as I understand it, officially been abolished for generals by this time, but as can be clearly seen in the painting which portrays the troop review on Åland in the summer of 1808, some officers still wore them.

The Black hussar set includes some horses and an attendant holding them for the top brass. I may or may not include these, and am currently pondering what sort of figure/figures to include as attendants, bystanders or guards. A Nyland dragoon or Horse Life guard would be appropriate, as these troops commonly performed guard duties at HQ as well as working as messengers etc. But the men serving as adjutants to the various generals were from a variation of different regiments, including some that took no other part in the actual fighting and whose uniforms I would therefore not have the opportunity to paint.

The only problem with using the beautiful Black hussar set is that the main figure, the field marshal, becomes problematic when you consider the fact that command of the army in the field was pretty much never exercised by anyone of that rank. Klingspor, who was the commander-in-chief, was never actually present on the field at any of the major battles. At one of them he was in fact having a cup of coffee at some manor house at a good safe distance away as the battle was being fought! However, I am happy to ignore that in order to make a good looking HQ set for my troops…

This is how the Livgarde figures turned out. There are some details that need to be adjusted, but this is what the basic figure will look like. It is not catastrophic, but I was more happy with the grenadiers, who where easier to model as well. But I suppose these work OK, especially if I can manage to do some nice looking officers to lead them. But painting these reminded me of why I dont like painting plastic figures that much… I just dont like the feel of plastics (the base figure is from the plastic Spanish box by Perry).

These figures are a simple conversion from the standard Perry miniatures Swedish infantry. I am pretty pleased with these and it doesnt seem unrealistic to convert enough figures for a couple of battalions, which is what I would need.

The paints used are: Coat d’arms Royal Blue, Cda Blood Red, Vallejo Gold Brown (sash), Cda Tanned Flesh and Cda Flesh.

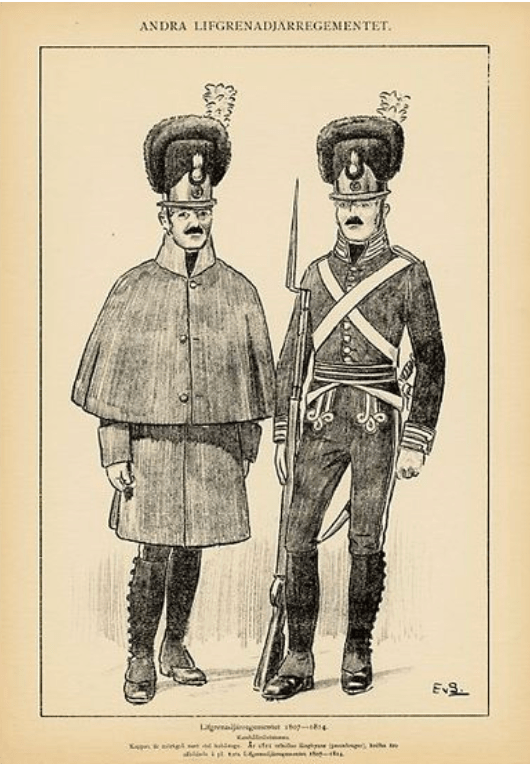

The regiment’s hat was distinctive and as you can see below, it was quite different from the guards’ hats that I discussed in my last post. The good thing about this hat is that its shape is so similar to the standard Swedish infantry hat that its is fairly easy to convert the figures. All you really need to do is remove some of the part on the left hand side where the hat has a fold and brass cordon (which the grenadier hat doesnt have) and then add the plume with a roll of green stuff which can then easily be given some texture with a sculpting tool.

Livgrenadjärregementet apparently had serious problems with the supply of uniforms in 1809. Not all soldiers had received the new (1806) uniform, presumably some would have worn the older 1792 version, which had a white collar and white trousers. Those uniforms were certainly very worn by that time. A few soldiers had the new greatcoats, as seen in the illustration above. Whether all soldiers had the new hat, I do not know. Some newly arrived recruits and reserves would have worn civilian clothes. All of this means that it might be reasonable to (for example) paint some soldiers with white, grey or brown trousers or even mix in one or two with civilian clothes.

In contemporary depictions, the confusion is no less apparent. Adelborg has a drawn a soldier wearing the 1806 uniform with the 1807 hat. The trousers lack the pattern and side stripe though. Also, that drawing may have been made later (even in 1814). The grenadiers did after all have 6 battalions, in what was in practice two regiments, and these units may well have had different uniforms. This was indeed the case later on (1816), when they were officially divided into the 1st and 2nd grenadier regiments.

In 1808, the Swedish army had several guards and grenadier regiments, with ever changing and sometimes confusingly similar names. However, only some of these troops took part in the war in Finland, and those that did did not play a key part. I will try to give an overview of the uniforms and flags of these regiments as they pertain to the 1808-1809 period (for the later Napoleonic period, uniforms changed, so this information will not be very useful for that period). First, I will concetrate on the foot guards.

In the Swedish literature, these regiments are sometimes grouped together under the title “Kungl. Maj:ts liv- och hustrupper”, “His majesty’s life- and household troops”, and they can be said to have had a certain status. However, among these troops were soldiers of different types, both enlisted (värvade) and alotted militia (indelta), so that some of them in practice were very similar to the regular alotted territorial regiments.

The foot guards regiments

Illustration A: Private, Finnish guards regiment, 1807; Private, Life guards regiment, 1807; Officer, Life guards regiment, 1807. One might think that this uniform was the one used in 1808, but that does not seem to have been the case. In fact, the jackets portrayed here were not issued to the troops until 1812. (Vinkuijzen collection, NYPL)

At this time, there were three guards infantry regiments: Livgardet (the Life guards), Svenska gardet (the Swedish guards) and Finska gardet (the Finnish guards). Because of later name changes and traditions, Livgardet is often called Svea livgarde, as the unit was later so called. Similarly, Svenska gardet is sometimes identified with the subsequent unit Göta livgarde. In Swedish, the names (Svea) livgarde and Svenska gardet are particularly easy to get mixed up, but they are and always have been different regiments. Indeed, I myself mixed the names up when writing this article (now edited).

The history of these regiments is quite complicated, but for our purposes it is sufficient to say that Livgardet was an old unit which had been functioning under the same name and similar organization since the 17th century. The other two regiments, on the other hand, originated in various enlisted regiments that went under different names during the 18th century.

To make matters worse, these regiments were renamed already during the course of the Finnish war. The king was so displeased with their performance at the landing at Helsinge in late September 1808 that he abolished their guards status and renamed them after their respective commanders. Livgardet became Fleetwood’s regiment and the Swedish and Finnish guards were merged into one unit called af Palén’s regiment.

The guards regiments had varied in size over time. Livgardet and Svenska gardet were both organized into two battalions each up until 1806, when they were reduced by more than half. By 1808 therefore, the three regiments only had one battalion of around 530 men each. These battalions participated at the landings at Lokalax and Helsinge in September. A weak battalion of Livgardet, by this time rebranded to its modern name, Svea livgarde, also participated in the battle of Sävar in August 1809.

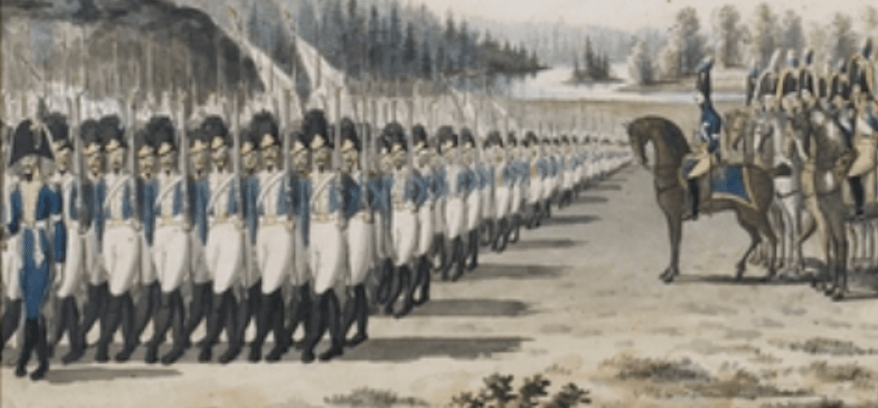

Illustration B: Guards battalions on parade before king Gustav IV Adolf on Åland, 31 July 1808. (Contemporary painting, in a Finnish museum somewhere…)

Illustration C: Official uniform plate for the Finnish guards, 1806. Note how the private on the right wears black gaiters and no epaulettes, just like the troops in the review on Åland (ill. B). (Riksarkivet/Krigsarkivet)

Uniforms

In the 1802 model, the guards regiments wore a jacket which was similar to that of the standard infantry uniform, with a few small details which distinguished them from other troops. The most distinctive feature was bands of white lace (silver for officers) on the front of the collar, on the cuffs and across the plastron. In addition, the jacket itself had longer tails than the standard Swedish infantry coatee (which was very short). The guards’ uniform also included white gaiters. However, in the field, black gaiters of the same type as those worn by the rest of the infantry seem to have been used. Similarly, the uniform jacket had epaulettes, which seem to have been omitted in the field (see illustrations B and C).

Furthermore, over time the distinctions between the regular infantryman’s uniform and that of the guards increased, as changes to the regular uniform did not affect the guards. When the plastron was removed from the regular infantry uniform in 1806, the guards retained them. And when the model 1807 uniform was introduced, all grey with dark blue facings, for all regiments, this again did not affect the guards. Neither does the change to grey trousers, in 1806, seem to have affected the guards. Apparently, the guard units also retained the older type of white waist belt, and did not use the blue-and-yellow sash of the regular infantry. Judging by the painting of the troop review on Åland, the guards battalions were still wearing the 1802 model uniform in the summer of 1808, but with the new hat. Some illustrations, such as those in the Vinkhuijzen collection (illustration A), show the uniform jacket open towards the waist, similar to French uniforms of the period. However, the offical plate of the model 1802 (illustration C) uniform as well as the Åland review (illustration B) show the jacket buttoned all the way down. Also, the waist belt seems to have been worn over the jacket (again, B and C), not underneath it (as in A). This accords well with Bellander (Dräkt och uniform (Stockholm, 1973), p. 407), who states that the new uniform with the open front was issued to the regiments only in 1812, and that the uniform and equipment depicted at Grelsby in the summer of 1808 is indeed of the 1802 model (but with the modern hats).

Another distinguishing feature of the guards was their headgear. In fact there was a plethora of different helmet- or hat-like creations for different guards and grenadier units of the Swedish army at this time, which also changed over time. The three guards regiments previously wore a bicorne, and the bicorne was still worn by officers of those regiments in 1808. However, the private soldiers wore a tall, rounded hat with a black plume which ran diagonally across the head (Illustration D). On the left hand side, the brim was folded up, and the company pom-pom and a tall white plume was fastened in a way similar to that of the regular Swedish infantry hat. The hat had a brass cordon with an emblem on the front. The emblem showed the royal emblem (three crowns inside a crowned blue oval) for the Livgardet; a lion over diagonally white-and-blue (Göta emblem) for the Swedish guard and (presumably) a Finnish lion on red background for the Finnish guard.

Illustration D: Hat, model 1807 of Livgardet/Svea livgarde. (Digitaltmuseum/Armémuseum)

All three guards regiments wore white buttons. The three regiments were distinguished by their facing colors. Livgardet wore yellow facings. The Finnish guards wore red turnbacks and plastron, but yellow collar and cuffs. The Swedish guards wore red facings. As can be seen in illustration C, the guards also had a brass plate on their cartridge box. Officer’s jackets were decorated with silver lace, while other ranks’ had plain white worsted lace bands.

Illustration B, which was drawn from life during the conflict, as far as I understand it, is interesting not only because it tells us something about how the uniform was worn in practice. It also shows an officer sporting an interesting variant of the uniform. The blue trousers do not appear in any other illustrations I have seen, as white seems to have been the regulation color for officers as well as men. There are similar trousers in other Swedish uniforms at the time (Horse Life Guards in particular), and several authors mention how officers took some liberties with regulations to deck themselves out as best they could. The officer also wears epaulettes, in contrast to the men (although mysteriously, the opposite is the case in ill. B!).

Extant uniforms

As these were guards regiments, it is not surprising that more items of clothing and equipment has been preserved from them than is usually the case in this period. The Swedish army museum in Stockholm has a large number of items which is identified being of Livgardet and Swedish guard provenance. However, the dating of these is problematic. However you look at it, the uniform jackets do not match the depictions in the plates above, if the museum datings are correct! On the other hand, there are a couple of jackets that do look very much like the one in the plate (m/1802, ill. C). Now, the uniforms of the guards did not change all that much in the years after 1809, but they changed slightly several times. So, it may be that these are indeed later jackets. But from my amateurish point of view, the livgarde uniform below looks very much like the 1802 in terms of the cut of the waist. In 1807, the jacket was open in the lower plastron. In the later model (1815), the waist was much more straight at the front.

Sappers/profosser, musicians

There are also some interesting items showing the dress and equipment of drummers and sappers, or rather profosser (provosts). The profoss in the Swedish army looked like the sappers of e.g. the French army, but were really a form of military police (or executioner…) rather than an engineer or carpenter. The profoss seems to have worn opposing colors, so that the profoss of the Livgarde, with yellow facings, wore red facings and a red-shafted axe, while the profoss of the Swedish guard (subsequent Göta), which had red facings, had blue-shafted axe. The profoss also wore a bear skin hat. Some of the equipment shown below is a bit later, but I assume the principle to have been the same. The profoss jacket however, is actually of the model 1802 (according to the museum).

There is a distinct possibility that Livgardet/Svea livgarde received new uniforms in time for the battle of Sävar in 1809, but after their participation in Finland in 1808 (the new 1807 model replacing the 1802). However, in this case, the uniform would at least have been very similar to the old one and the hat would have been the same.

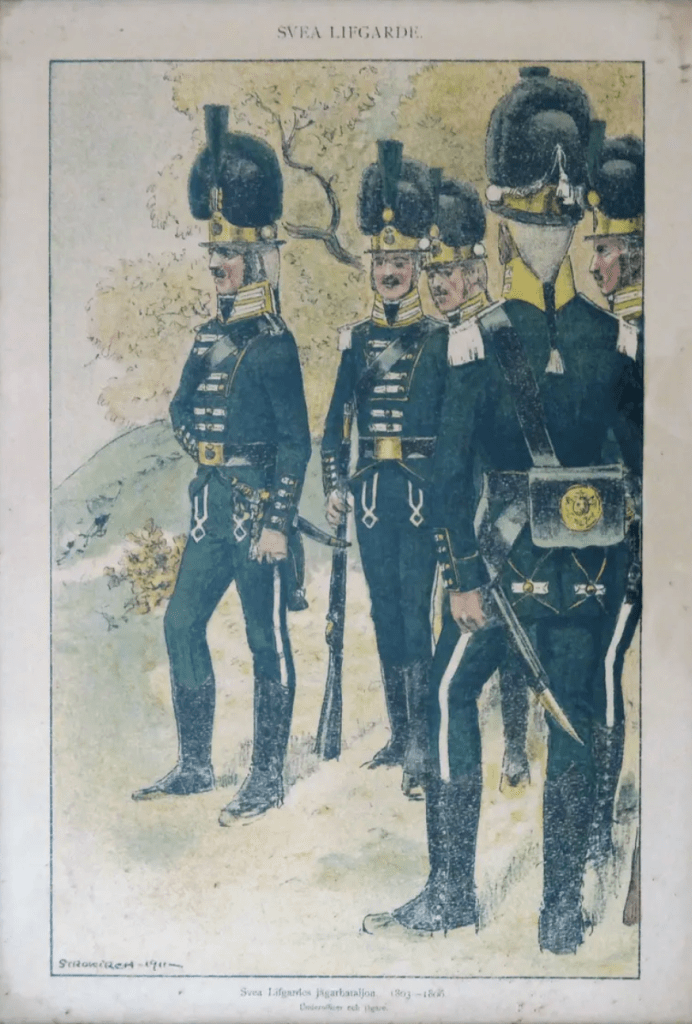

Jägers

If you thought that the standard guards uniforms look a little weird, you should see the guard jägers! As with other regiments at the time, the guards regiments had their own, integral jägers. However, in contrast to regular line regiments, where the jägers were chosen on campaign and marked out with different colors to their plumes and blackened belts, the guards jägers had a (very) distinctive uniform and hat. This was green, with white facings or piping. The hat was similar to the standard guards hat, but had the plume on the front instead of on the side. I would like to thank Traveller on the Lead Adventure Forums for reminding me of the jäger uniforms.

Flags

In contrast to the uniforms, the flags for the grenadier and guards regiments are quite uncomplicated. Most of them carried flags of the same type. The king’s colors (livfana) were the same as the regular infantry, only with a small crown in each corner. The company colors featured the royal monogram instead of the royal emblem, but were otherwise the same as the king’s colors.

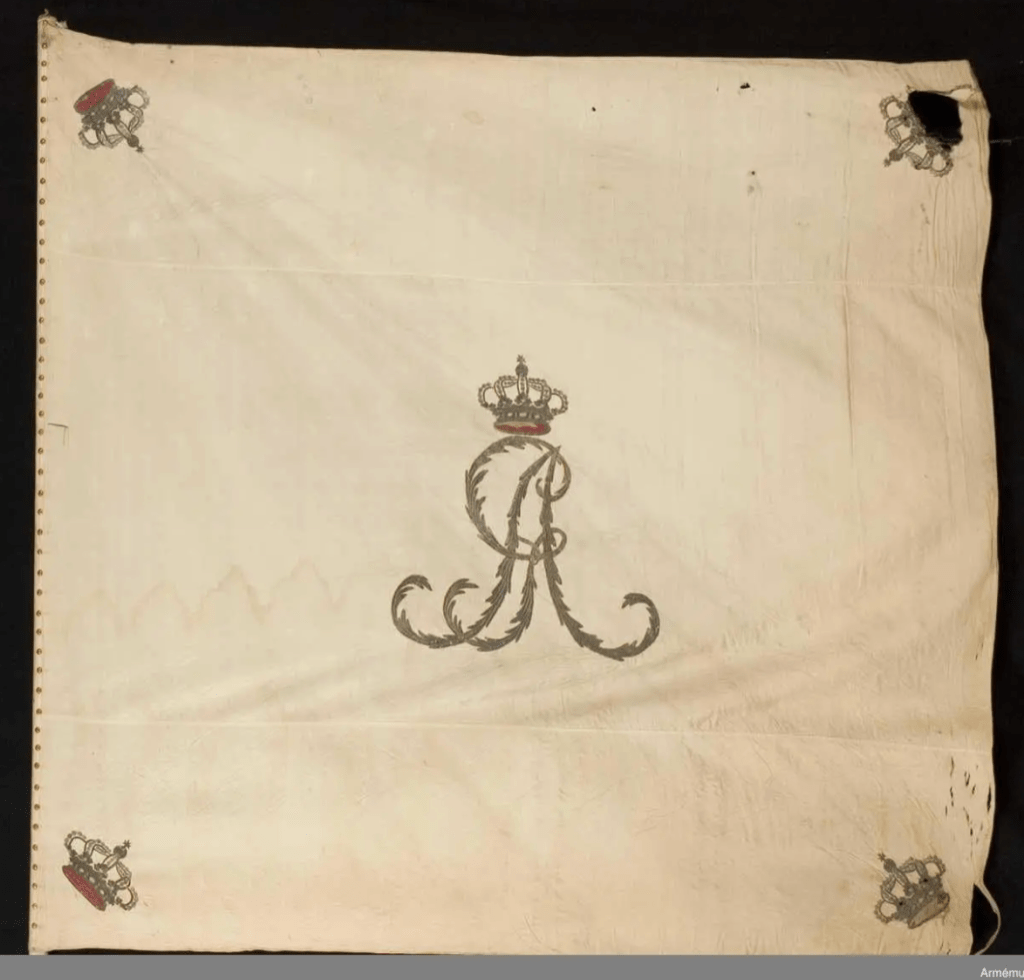

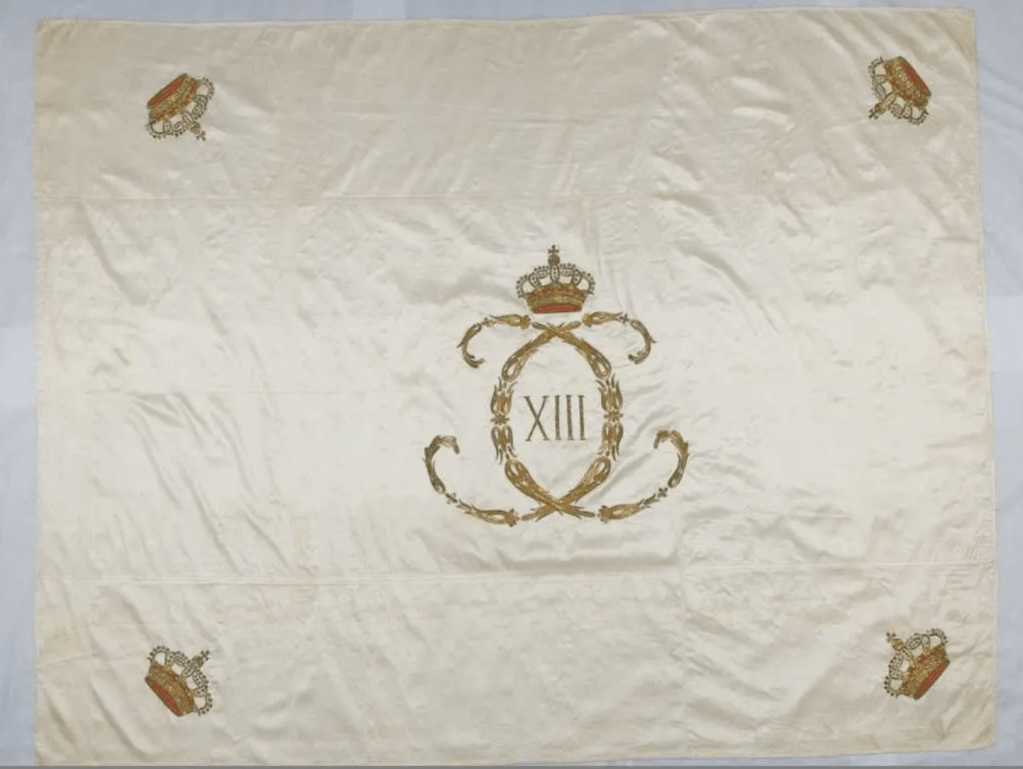

Illustration H: Company colors of a guards or grenadier regiment (left); king’s colors of a guards or grenadier regiment (right). (Digitalt museum/Armémuseum)

When the guards were demoted in late 1808, new flag designs were created (as the guards flags clearly marked their status) (Illustration I). Whether these new designs were ever used I do not know, but they are elegant. It seems unlikely that they would have been used at the battle of Sävar. By then (in August of 1809) the king had been deposed and his successor had already been crowned. The humiliating demotion of the guards was indeed a contributing factor, although probably a minor one, to the deposition of the king. It is therefore more likely that they carried the old flags, but modified so that the emblem of Gustav IV Adolf was replaced by that of Carl XIII. Such modifications seem to have been quite common and were probably relatively easy to make. This happened again, when Bernadotte (Carl XIV Johan) succeeded Charles as king in 1818 (Illustration J). The only reference I know of is Törnquist, who states that both guard regiments had relatively new flags at the time and that the old ones (with Gustav IV:s monogram) were only replaced in 1810. (Leif Törnquist, “Colours, Standards, Guidons and Uniforms, 1788–1815”, in Between the Imperial Eagles (Stockholm, 2000), p. 146).

Illustration I: Proposed company colors of the Fleetwood and af Palén regiments (1808). (Riksarkivet/Krigsarkivet)

Illustration J: Company colors of guards regiments, 1809 and 1818 (Queen’s Life regiment and unknown guards regiment). (Digitalt museum/Armémuseum)

Figure availability and modelling ideas

Perry miniatures do not make any figures for Swedish guards at the moment. Lets hope that they decide to make them at some point in the future… But until then, one has to make do with some sort of conversion. My plan is to try to combine the heads of the Perrys’ Värmland jägers with bodies taken from their recent Spanish plastic infantry. The Värmland jägers have a hat which has the same shape as the guards’ hats, and should do nicely. The plastic Spaniards have most of the elements that I need for the rest of the uniform: plastron, gaiters, similar length of jacket (I think!?). I will need to add waist belts with greenstuff, but there shouldnt be that much else.

I should also mention that Eagle figures sell Swedish guard figures in 28mm. However, these are both quite dissimilar to the Perry figures in style, but more importantly, correspond more to 1813 and later periods. Elite miniatures and Steve Barber have ranges of Swedish napoleonics, but they are clearly for the later period and also have no infantry with guards or grenadier headgear. Connoiseur miniatures (sold by Bicorne) have Swedish grenadiers, but I do not know how these figures look and therefore not how they would work as guard figures. There is a website (digitalsculpt.se) which sells loose heads (resin) with the guard hat which could be an option for anyone who wants to kitbash together guards at a reasonable price.

There are likewise figures in smaller scales. There are 15mm figures by Naismith designs (not sure these are currently in production?), which look OK. There are also 15mm by Blue Moon; the figures labelled “grenadiers” could be used, although they have a single row of buttons on the jacket which is wrong, but perhaps not impossible to cut away with a knife. Blue Moon are otherwise good in that they wear clearly modelled gaiters. Old Glory 15:s look like they could also be an option. I dont paint 15mms and dont have these figures to hand and therefore cant really comment on the quality of the figures based merely on pictures.